This is third installment of Jim Hislop’s fascinating history of the farms that made up Woodstock. You can find Part 1 here, and Part 2 here and our general Woodstock history here.

Few people may realise when they take the Church Street offramp from the N1 into Woodstock, as they drive along busy Albert Road towards the Biscuit Mill, that they are passing the site of an historical landmark.

In 1788 Pieter van Papendorp used his cottage between the Castle and Salt River as security for a mortgage bond. A silversmith by trade, Van Papendorp (after whom Woodstock was originally named) lived in another house on this property, probably a simple fisherman’s cottage originally (the sea ran very close to the present Victoria Road, just in front of the railway line and Castle Brewery building), which was built sometime in the first part of the 18th century or possibly even the late 17th century.

This homestead, called Papendorp House when he lived there, was later renamed La Belle Alliance. It was outside the old thatched cottage, under the shade of a wind-battered milkwood tree, that the Dutch signed over the fortifications at the Cape to the British in 1806 – after Governor General J.W. Janssens’ (picture 1) garrison was defeated at the Battle of Blaauwberg. After this historic event, the cottage and nearby milkwood became known as the Treaty House and Treaty Tree respectively.

Later the house was owned by a tanner named John Brown, but he went insolvent in 1832 and was forced to sell the property, which also included a tannery. Though the spot was fairly windswept during summer Southeasters (sea sand whipping residents’ faces as they dashed for cover), the cottage must have had a fine view of Table Bay, and sailing ships would have literally passed by close to its front door.

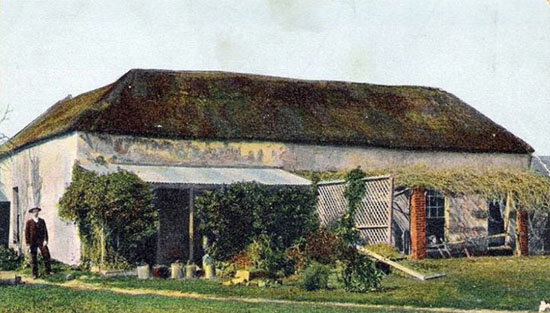

The oldest structure in the area, the Treaty House survived well into the 20th century, but with the increasing amount of industrial activity in the Woodstock area at the time, space was at a premium and it was decided to demolish the homestead to make way for a factory in 1935, its historical significance not being enough to preserve an old building in those pre-War days. Luckily, because of its importance, the house was depicted by various artists, including John William George (picture 2) during its final decades, and some photographs of it exist, too (pictures 3 and 4).

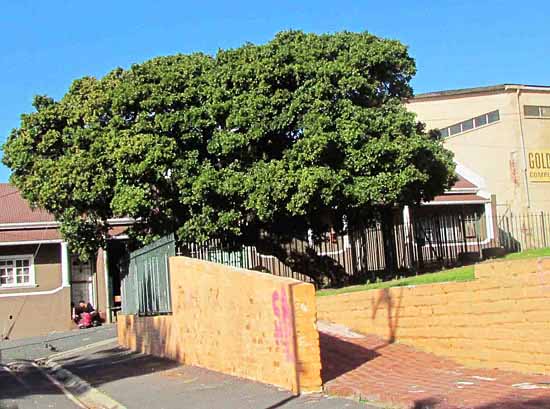

The centuries-old tree somehow survived, standing stubbornly forlorn and forgotten on a derelict plot on the corner of Spring and Treaty Roads (just off Albert Road), the remainder of the square that once flanked the old cottage. It’s not exactly clear how old the milkwood tree is, but some say it was a landmark for Portuguese sailors in the days before the Dutch landed at the Cape in 1652, even being old enough to have ‘witnessed’ the Hottentots killing 64 of the cut-throat explorer Captain d’Almeida’s infamous marines, who had abducted a Khoisan baby nearby in 1509! What is more certain is that slaves were sold under its shade (and sometimes hanged from it). The tree has definitely seen a lot of Cape history pass by, from the end of slavery in the 1830s to the reclaiming of large parts of Table Bay a century later.

Luckily, in 1966 the Cape Town City Council took possession of the remaining plot and the ancient tree, and it was proclaimed a National Monument in 1967. The milkwood is still there, now fenced off to protect it, bent and gnarled from centuries of howling gales. It’s probably the only tree in South Africa to have a wine named after it – Flagstone’s Treaty Tree label (picture 5). It’s a great shame that the rustic, old U-shaped house with its thatched roof, heavy-raftered ceiling, stone-flagged floor and vine-covered stoep no longer exists, as it could have made a fantastic centrepiece for Woodstock’s current rebirth.

For a souvenir download of the Treaty House, visit the Old Castle Brewery website.

Sources:

1. http://battle.blaauwberg.net/the_treaty_house.php

2. The Cape Odyssey No.35 (Feb/March 2004)

Jim Hislop is the current Senior Copy Editor and Wine Writer for Pick n Pay’s Fresh Living magazine.

A long-time resident of Observatory, he is also a member of the Vernacular Society and is currently researching the history of the old farms of the Observatory and Woodstock area.